As we go into 2021, we all want to know what we can do to maximise our students’ learning opportunities. Does everyone need the same kind of instruction? What should we be doing to overcome any pre-existing achievement gaps? How do we find out where to start?

Assessments can inform our plans for recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and help us decide on the best instructional strategies for our students. The right assessments can provide us with a roadmap for the journey—ensuring we know what to do and how to do it.

The need for accurate, formative assessment has never been greater.

We need to refocus our efforts to ensure that any actions we take have maximum impact on learning and achievement.

We should focus on the things that can have the greatest impact and stop being distracted by the things that don’t matter.

So how do we do what Professor Hattie recommends?

We need to answer this question:

What is the purpose of assessment?

Effective assessment should help us:

-

Find out what students already know

To do this we need to know what they should know, and this must form the basis of any assessments we use.

We need this data to provide an understanding of the ‘state of the nation’ or the ‘state of our classroom’.

-

Find out what students don’t know

The assessments used should do more than measure outcomes. They should be able to be analysed to such a degree that teachers know what and where the gaps are and why students aren’t achieving as they should. What students don’t know must inform instruction.

We need to critically analyse data to ensure instruction meets students’ needs so that it has the greatest impact.

-

Measure the impact of instruction

Assessments should be used to show how instruction has worked to close the gaps and improve outcomes. The efficacy of instruction must be measured.

We need to know that what we are doing is working. If it has not made enough difference, we need to change our instruction and repeat the process of instruction and evaluation.

Case study—using assessment to drive instruction

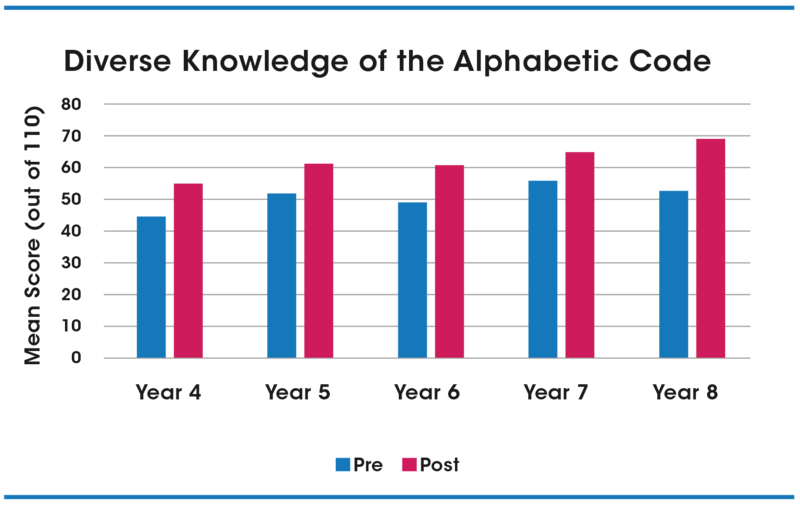

In 2019, approximately 1000 Year 4 to 8 students undertook an assessment that measured their knowledge of the alphabetic code of English. Most, if not all of these students had been taught using some sort of phonics programme in their early years, and all were reading and writing independently, although not all were achieving at age-appropriate expectations.

What were we assessing and why?

The NZ Ministry of Education expectations for writing after one year at school (Literacy Learning Progressions) are that students should be able to write most sounds of English one way.

Because most sounds of English can be written in more than one way, it seems appropriate to expect that after four or more years at school, students should not only be able to write the sounds of English in one way, but they should also know other ways of writing them as well.

Why is knowledge of the code important?

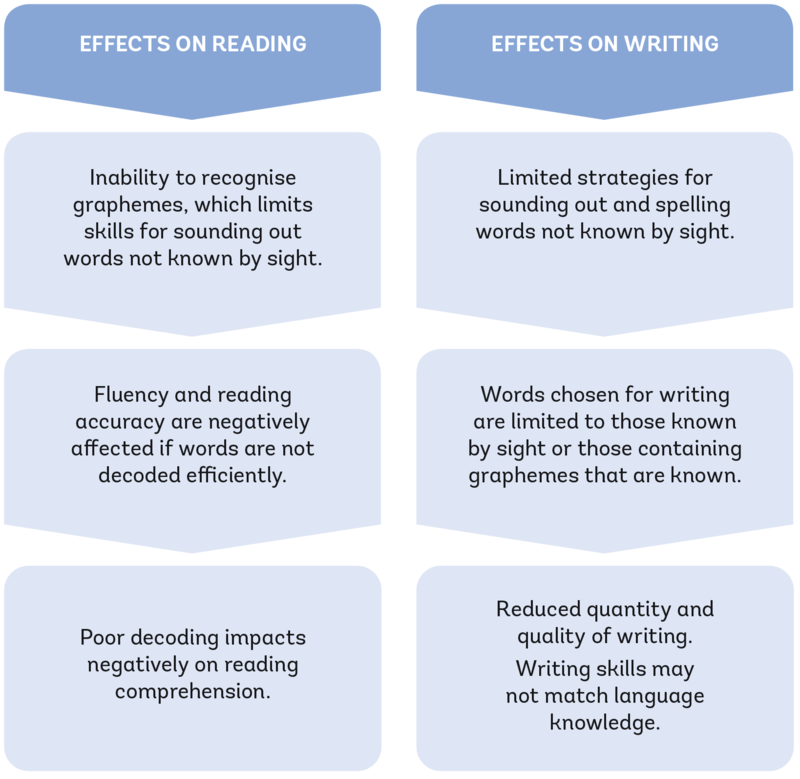

A lack of knowledge of the alphabetic code has a negative impact on reading and writing outcomes.

What did our assessment show?

| Year Level | Percentage of Students |

|---|---|

| Year 4 | 1.6% |

| Year 5 | 2.96% |

| Year 6 | 1.18% |

| Year 7 | 3.91% |

| Year 8 | 7.02% |

How many students could write all the sounds of English one way?

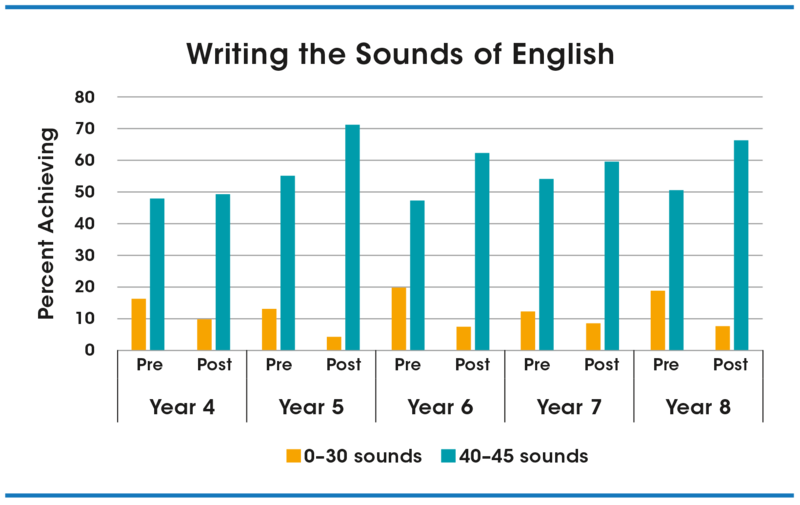

These results shocked teachers who expected about three-quarters of their students to be able to do this. What was also worrying was that between 12% and 20% of students across these year levels scored less than 30 out of 45. That means there were 15 or more sounds they could not write at all!

| Year Level | Percentage of Students |

|---|---|

| Year 4 | 39.84% |

| Year 5 | 58.13% |

| Year 6 | 56.81% |

| Year 7 | 70.04% |

| Year 8 | 61.94% |

How many students could write sounds in different ways

(they got 50 or more out of 108)?

Large numbers of students could not accurately write the sounds of English in one or more ways. The assessment data showed that there was work to be done!

Assessment-driven instruction

The Catch Up Your Code assessment shows exactly which sounds students can write in one or more ways. Teachers could have just chosen to work with the sounds of English that needed the most instruction, but because of the surprising results of the assessment, most teachers chose to work with every sound of English in a systematic way, spending 10 minutes a day over 10 weeks catching up this code knowledge.

What happened?

Results improved across the board—the number of students with significant gaps in their knowledge (those unable to write 15 or more sounds) dropped, and the number of students being able to write most sounds (40 or more) rose.

Students’ results for writing sounds in different ways also rose across all year levels.

What was the impact of instruction?

We used John Hattie’s Effect Size Shift to measure of the impact of instruction. The Effect Size Shifts for all five groups show significant progress after explicit instruction.

| Year Level | Effect Size Shift |

|---|---|

| Year 4 | 0.7 |

| Year 5 | 0.6 |

| Year 6 | 0.7 |

| Year 7 | 0.6 |

| Year 8 | 1.0 |

Some broad guidelines for understanding Effect Size Shifts:

0.15–0.45 — small to medium impact: up to two times the normal rate of learning

0.45–0.75 — medium to large impact: two to three times the normal rate of learning

0.75+ — large to very large impact: three-plus times the normal rate of learning

The data show that all five groups experienced two to three-plus times the normal rate of learning when they used Catch Up Your Code.

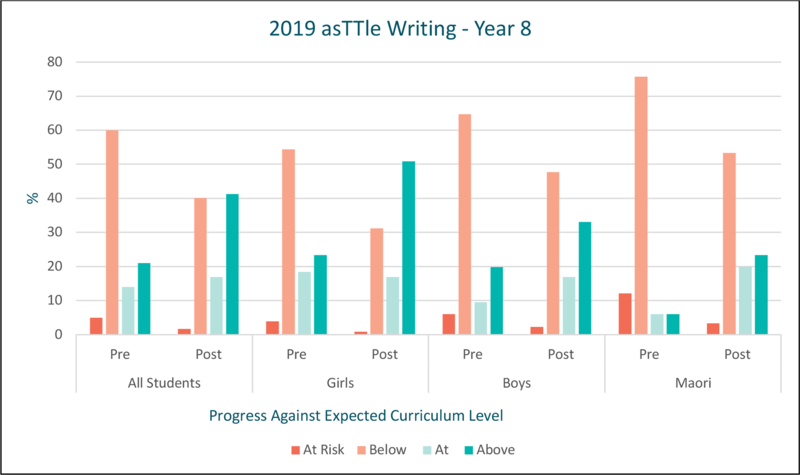

The following graph shows the improvement in writing for approximately 200 Year 8 students after Catch Up Your Code instruction over a 4 ½ month period, using the e-asTTle writing writing assessment (a NZ Ministry of Education online assessment tool used to assess writing from Years 1 to 10).

Once again, progress was obvious across the board—the number of students in the ‘below’ and ‘at risk’ groups dropped (those below or well below year group expectations), and the number of students at or above expectations increased.

Seeing evidence of the success of instruction was exciting! To be able to look at an Effect Size Shift that tells you your students’ progress is two to three times the normal rate—because of your teaching—is inspiring!

What can we learn from this case study?

Choosing assessments that are relevant to your students’ needs—those that allow you to find out what they know and where the gaps are—and choosing resources that ensure effective instruction, will maximise the impact of teaching on students’ learning and achievement.