It is widely acknowledged that literacy instruction — and in particular, foundational literacy instruction — needs to be structured, explicit, and systematic. The majority of the research bears this out, and most teachers would agree as well. So what could be the problem?

There is nothing inherently wrong with systematic instruction. The problem is simply that being systematic is not enough.

The word systematic is defined as anything that is methodical in procedure or plan. There is no doubt that literacy instruction needs to follow a plan and be methodical and structured. It needs to include direct, explicit instruction that is evidence based.

But what most programmes lack is clear instruction that helps students understand how the systems of written English actually work. They may be systematic, but they don’t teach the systems.

"The less easily a child intuits the structure of words, the more vital is direct, systematic, long-term instruction in how our writing system works."

Keeping the system in systematic

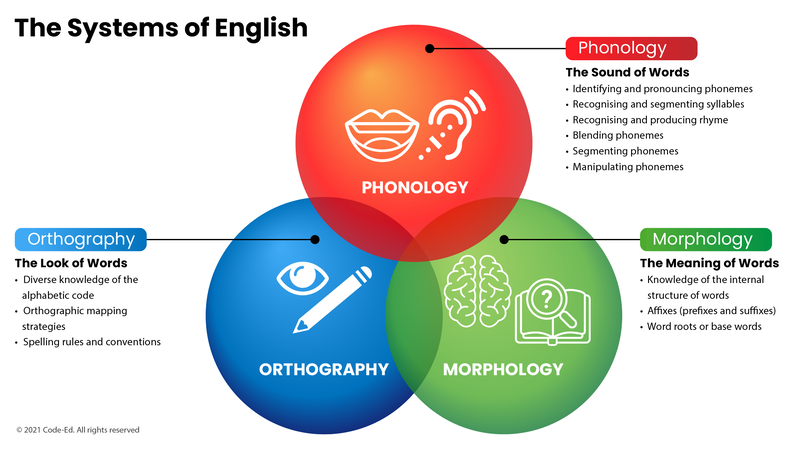

A system is a regularly interacting or interdependent group of items forming a unified whole. In the English language, there are three systems that interact together to determine how we pronounce, write, and understand the meanings of words.

It is knowledge of these three systems and how they interact that provides students with an understanding of written English. Without that understanding, students will find it difficult to understand how words work, regardless of how systematic their instruction may be.

Effective literacy instruction must use a systems-based approach that links sounds, spelling, and meaning.

"The major goal of the English writing system is not merely to ensure accurate pronunciation of the written word—it is to convey meaning."

What’s the difference?

It is possible for instruction to be both systematic and systems-based. Unfortunately, literacy programmes that do both are the exception rather than the rule.

This might sound complex, but it's actually quite simple. Much of the same content is taught, and in a similar order. It's the approach to the content that differs, working from the known to the unknown, which for young children means starting with oral language.

What does systematic literacy instruction usually look like, and how does it differ from systems-based literacy instruction?

Systematic instruction about the alphabetic code might look like this…

-

Instruction is usually based on teaching from graphemes to phonemes (spellings to sounds).

-

Students learn that graphemes (individual letters and letter patterns) represent particular sounds.

-

Letters and other graphemes are taught according to a structured scope and sequence.

-

The approach is systematic in that it teaches a series of graphemes, starting with single letter-sound graphemes, then double-letter graphemes, consonant digraphs, vowel digraphs, and so forth.

-

The approach teaches English grapheme-phoneme relationships in a methodical and structured way. But teaching these details does not mean students understand the systems they relate to.

Example

Students learn that each grapheme represents a particular sound. Any ‘exceptions’ to this rule are saved for future instruction. For example, students learn that ‘a is pronounced /a/, as in Ann', not that a is a letter we can use to write the /a/ sound (and some other sounds as well). The difference is subtle but important. Learning this way makes it difficult for students to interact with anything but the most controlled decodable text, to say nothing of poor Amy, Archie, Andre, and Alexis, whose a's don't follow the rules!

Students do not learn to expect that graphemes can be pronounced in different ways, and they may not be taught that phonemes can be written in different ways — critical concepts about print that many students of all ages do not understand.

Systems-based instruction about the alphabetic code looks like this…

-

Instruction is based on teaching from phonemes to graphemes (sounds to spellings).

-

Students learn that sounds can be written in various ways with different letters or groups of letters.

-

Sounds and the ways we write them are explored according to a structured scope and sequence.

-

The approach is systematic in that it teaches the sounds of English, starting with sounds that are written more reliably (with single or double letters) and moving on to sounds with more diversity in the way they can be written.

-

The approach teaches English phoneme- grapheme relationships in a way that links to the way the systems of written English evolved. It teaches how the code works, not how individual graphemes work.

Example

Students work with words that come from their own oral language and discover the

spelling patterns used to write them. In doing so, they learn that the same sound

can be written differently in different words (e.g. Tia has a t for her /t/,

Thomas has a

Students learn that individual letters can represent sounds, and so can letter clusters. They also learn that letters and letter patterns can be pronounced differently (t can sound like /t/ in Tamati but when it’s followed by h it sounds like /th/ (unvoiced) in Beth and /th/ (voiced) in that).

The benefits of a systems-based approach

Learning that a sounds like /a/ (which is true when it’s true) does nothing to teach the system of the alphabetic code. It teaches an isolated piece of information that only works some of the time.

When students learn about the alphabetic code this way, they encounter words that ‘don’t follow the rules’ they are expecting. They often get frustrated and come to believe that reading and spelling is too difficult because what they have just learned doesn’t always work. They think there is an endless list of rules — which all have exceptions — that they have to memorise.

In contrast, students who systematically explore sounds and their spelling patterns in a systems-based approach come to believe that written English is governed by patterns and rules that fit together in a system that makes sense and that they can understand. Finding the system becomes an exciting challenge!

"The knowledge about symbols, speech sounds, and meaning actually supports the memory of whole words and helps with reading."

If students are taught to understand the system that the alphabetic code is based on from the outset, they will not be confused when they find a letter does not sound the way they expect it to. They will just think ‘it must have another sound’.

Teachers who use a systems-based approach can also teach students to decode words using any book — not just books designed to scaffold decodability. For example, when a student is unable to read a word, you can use strategies such as these:

| Systems-based decoding strategies | |

sun |

In this word, every letter has its own sound.

What are the sounds.? /s/ /u/ /n/ |

spoon |

In this word, the oo sounds like

/ōō/ and the other letters have their own sounds. |

straight |

In this word, the aigh sounds like /ā/ and the other

letters have their own sounds. |

capture |

This word has two syllables. (Cover up the

second syllable and point to cap.) |

widest |

This word has two syllables. (Cover up

the second syllable and point to wi.) |

Learning to decode words using decodable books scaffolds the decoding process. However, decodable texts are very different from other kinds of instructional texts, and some students struggle to transfer the decoding skills they learned using decodable texts to reading ordinary texts.

Teaching decoding using an approach that is both systematic and systems-based provides students with strategies and knowledge they can apply when they meet unfamiliar words in any text, whether it is decodable or not. It makes the process of decoding obvious — the learner knows what they are doing and why they are doing it. It also means young readers can use decoding as the first line of attack for reading unfamiliar words — something we know is the best strategy to use in any text.

So…what’s the problem with systematic instruction?

Systematic instruction is necessary, but to be effective it must also be systems-based. Teaching the alphabetic code in a way that is both systematic and systems-based provides students with strategies and knowledge they can apply when they meet unfamiliar words. It links the sound, the spelling, and the meaning of words in a way that makes sense. This provides students with a framework for understanding the process they are using, not just the details they are learning.

When you explain the system, students will find and remember the details.

Give them the details only, and they may never find the system!

I have been using this systems-based approach to teaching students the foundations for learning to read, write, and spell English for more than 20 years.

You might think this is too hard for beginning readers and writers — it’s not!

About the author...

Author and educator Joy Allcock, M.Ed., has spent her career developing resources that build a bridge between research and practice, ensuring that teachers have access to research-driven methods that really work.

Joy has dedicated her work to finding simple ways to teach the complex code and structure of written English. She has also led a number of research projects (most recently the Shine Literacy Project), which together have shown remarkable results for learners of all ages and backgrounds.