Have you ever had students who can read words like they and was, but they spell them thay and woz? These spellings are common when young children are learning to sound out and spell words, but some students continue to spell known and unknown words this way, sometimes for years. They might even spell words correctly in a spelling test, but when they are writing they revert to the sounding-out spelling. Why does this happen?

The young child who learned to spell they as thay didn’t spell it by visualising it, they wrote it by sounding it out and writing the sounds they heard — writing /th/ with th and the long /a/ with ay, which is a familiar pattern for the long /a/ on the end of a word.

Many students continue to think about the words they ‘hear’ in their heads as they write rather than the words they ‘see’ in their heads, which means their natural inclination is to write the sounds they hear in words rather than retrieve images of whole words.

So, in a spelling test a student may be able to think about one word and the way it looks, but as they write they are multi-tasking and revert to spelling words the way they sound. They may also have written words like thay and woz hundreds of times and simply spell it this way out of habit.

A continuum of thinkers

Research provides a way of understanding why people tackle spelling and reading differently (Baron and Strawson1, Treiman2). These researchers differentiate between Chinese and Phoenician processors to explain the different approaches people use as they read and spell.

The Chinese language is a pictographic language — you read it by storing the visual images of the characters that represent words, so it relies on developing a strong visual memory for them.

The ancient Phoenicians came up with an alphabetic code where the sounds in words were represented by symbols, so it relies on understanding the sound-spelling code for writing and reading words.

Most people use both sorts of processing strategies, but some learners at either end of the continuum have a strong preference for the visual memory or sounding-out approaches.

Chinese thinkers

People using Chinese processing strategies rely on remembering what words look like to help them read and spell unfamiliar words. They recall what other words with similar sounds or meaning look like. They might spell awesome like this — awsome, associating it with the word awful.

Teaching strategies that go from print to sound will suit these learners.

For example:

Think of all the words you can that contain the ough pattern and work out the different

ways it can be pronounced.

Phoenician thinkers

People using Phoenician processing strategies rely on understanding how sounds are written in words. They rely on knowing the connections between sounds and letters to sound out words, rather than recognising whole word images. They might spell awesome like this — ausum.

These students respond better to teaching strategies that work from sounds to print.

For example:

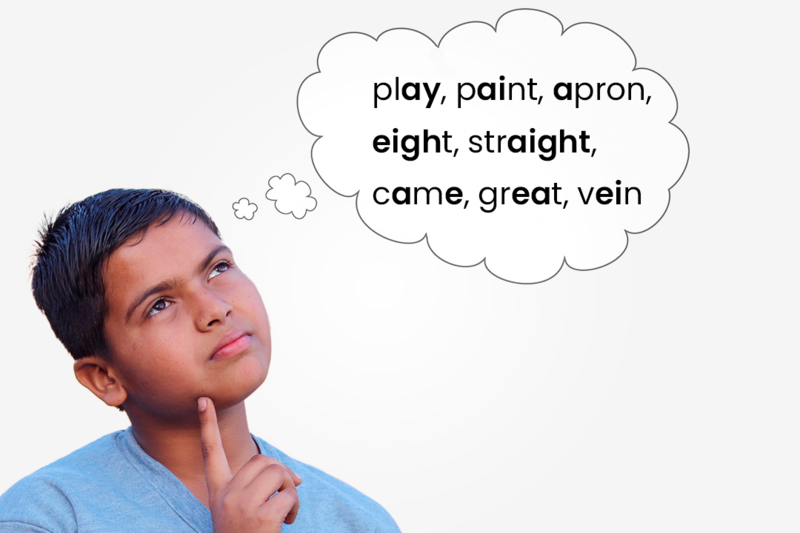

Think of as many words as you can think of that have the long /a/ sound. Find what that

sound looks like in these words.

How can we support beginning ‘thay’ spellers?

The following strategies will help all beginning students because they highlight the sounds that make up words and the code used to write them. All beginning writers, whether they have Chinese or Phoenician strengths, need this knowledge.

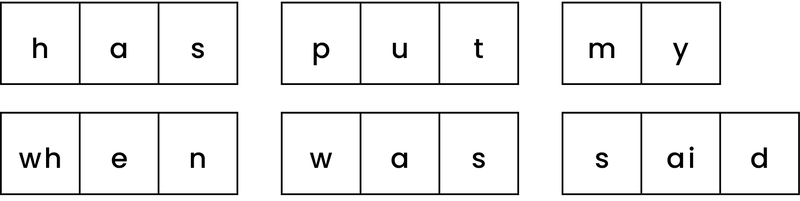

Beginning writers tackle writing words that they don’t know how to spell by writing the sequence of sounds they hear. They may write thay, woz, sed, poot, wen, haz, mi, and so forth. It is important that they do not practise writing high-frequency words incorrectly because this very quickly reinforces the incorrect spelling and becomes automatic.

Step 1: Acknowledge what the student has done correctly.

For example: A beginning writer has written they as thay.

Say: How clever are you! You have written both sounds in they the way they could be

written. You’ve put th for /th/ and ay

for the long /a/. You’ve spelled the long /a/ sound the

way we do in lots of words like Monday, Tuesday, play.

Step 2: Identify the part of the word that needs to change.

Say: In the word they, the long /a/ sound is written with an ey, not an ay, so they looks like this — th for /th/ and ey for the long /a/.

Step 3: Suggest strategies for remembering the part of the word that was not correct.

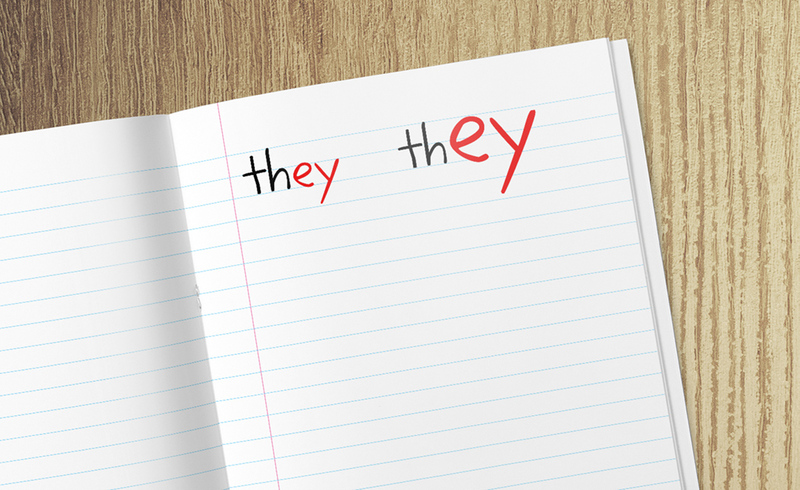

Say: Let’s put that word in your spelling notebook, and we’ll write the ey in a different colour (or bigger) to help you remember how to spell the long /a/ sound in they.

You can use the same approach with any high-frequency words. Highlight the spelling patterns in different colours or different sizes or write them in Elkonin boxes.

How can we support older ‘thay’ spellers?

Older students who have been writing high-frequency words incorrectly for years are likely to be unaware of the way they spell them as they write. If you asked these students to spell the word they aloud, they may well say t h e y, but they continue to write thay without noticing the incorrect spelling.

This is not because they are lazy or don’t care. It is simply that they have written the word incorrectly for so long it has become an automatic process. Explaining the way they taught themselves to spell these words as young writers, and showing how easy it is for incorrect spelling to become a habit will help relieve the sense of embarrassment and shame that many older spellers feel when they make errors with these high-frequency and seemingly simple words.

Step 1: Provide students with a strip of cardboard — like a bookmark.

Step 2: Ask them to find the high-frequency words they commonly misspell in their writing. (Some students may need help with this.)

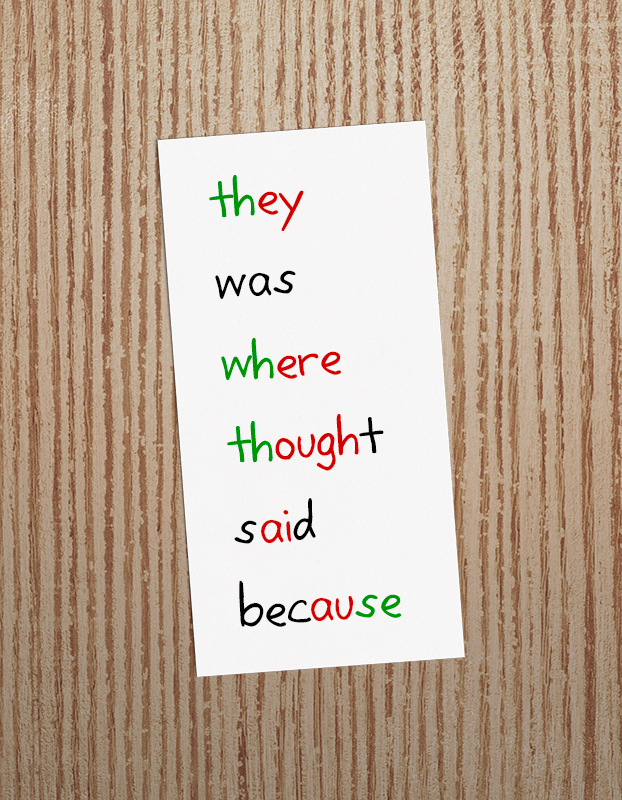

Step 3: Write these words on the bookmark, spelled correctly. Use colour-coding strategies to highlight the alphabetic code — black letters for one letter-one sound graphemes, green for consonant digraphs (e.g., sh, th, ng) and red for vowel digraphs (e.g., oo, ei, oa), trigraphs (e.g., ere, igh) and quadgraphs (e.g., ough, eigh). You can also use the strategies in the section for beginning spellers above for Phoenician spellers, to help them remember how to spell words.

Step 4: At the end of every writing session, allow five minutes for students to go through what they have written to look for these specific words, using the bookmark to correct them. Initially, correcting these words is a proofreading task but after doing this for a relatively short period of time many students spontaneously begin to correct the words as they write them.

Errors are our clues

Many of the strategies used in our classrooms — spelling lists and memorizing sight words, for example — favour the Chinese processor, who relies on visual memory to read and spell words.

The ‘thay’ speller who keeps spelling words like this is likely to be on the Phoenician end of the continuum, in which case more memorization is not likely to help. Instead, these learners need help learning to recognize and use the alphabetic code.

The young ‘thay’ speller shows that they understand the alphabetic principle — that words are strings of sounds that we record with letters and letter patterns. Their ‘error’ is something to celebrate!

The older speller who continues to spell they ‘thay’ is also showing the same understanding. If learning to spell they in a spelling list has not worked, this ongoing ‘error’ tells us we need to change the strategies we are using to teach. This ‘error’ is also something to celebrate because it gives us the clues we need to differentiate our instruction.

References

- Baron, J. & Strawson, C. (1976). Use of orthographic and word-specific knowledge in reading words aloud. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human perception and Performance, 2, 386-393.

- Treiman, R. (1984). Individual differences among children in spelling and reading styles. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 37, 463-477.